The Woodturning Lathe: A Brief History

The lathe is among humanity's oldest and most important machine tools. It can shape, drill, bore

and grind. In

Turning and Mechanical Manipulation, Vol. I

, John Jacob Holtzapffel

terms the lathe 'the engine of civilization'. He points out it is unique among machine tools in

that not only is it the only machine capable of replicating itself, but it is also capable of

manufacturing all other machine tools.

The lathe most likely evolved from the potter's wheel and the bow drill, which may have been used to

bore holes even before fire was discovered. In fact, fire may have been accidentally discovered by

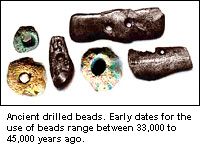

someone trying to drill a hole in a piece of wood. The presence of stone, shell, ivory and bone

beads with what appear to be drilled holes suggests that the bow drill may have been used as early

as the Late Stone Age.

The lathe most likely evolved from the potter's wheel and the bow drill, which may have been used to

bore holes even before fire was discovered. In fact, fire may have been accidentally discovered by

someone trying to drill a hole in a piece of wood. The presence of stone, shell, ivory and bone

beads with what appear to be drilled holes suggests that the bow drill may have been used as early

as the Late Stone Age.

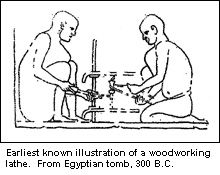

The Egyptians are believed to be the first to use lathes, as evidence of a round tenon joint was

found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun dating back to 1350 B.C. Moreover, the earliest known

illustration of a lathe is a drawing in an Egyptian tomb dating back to 300 B.C. The drawing

depicts one man holding a cutting tool while another uses a cord to rotate the workpiece back and

forth. The Egyptians also developed the bow lathe which could be operated by one individual. Two

pointed pieces of wood supported the workpiece and a bow with its string wrapped around the work was

used to turn it. The turner used one hand to move the bow forward and backward, while his foot and

other hand steadied the cutting tool. Cuts could only be made on one-half of the motion, when the

wood was spinning counterclockwise toward the turner.

The Egyptians are believed to be the first to use lathes, as evidence of a round tenon joint was

found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun dating back to 1350 B.C. Moreover, the earliest known

illustration of a lathe is a drawing in an Egyptian tomb dating back to 300 B.C. The drawing

depicts one man holding a cutting tool while another uses a cord to rotate the workpiece back and

forth. The Egyptians also developed the bow lathe which could be operated by one individual. Two

pointed pieces of wood supported the workpiece and a bow with its string wrapped around the work was

used to turn it. The turner used one hand to move the bow forward and backward, while his foot and

other hand steadied the cutting tool. Cuts could only be made on one-half of the motion, when the

wood was spinning counterclockwise toward the turner.

The bow lathe soon gave way to the spring-pole lathe, another type of lathe used by the ancient

Egyptians. One end of a rope was fastened to the end of a tree branch, extending downward, making

one turn around the workpiece. The lower end of the rope was then tied to a loop that served as a

treadle that the turner pressed down with his foot to rotate the work. Although cuts could still

only be made while the wood turned in a counterclockwise direction, the pole lathe was a definite

improvement over the bow lathe. It afforded a more rapid rotation and the turner now had both hands

free to hold the cutting tool.

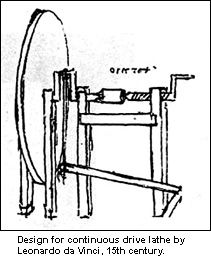

Pole lathes continued to be used almost unaltered from about 500 B.C. into the late Middle Ages,

until the inefficiency of its reciprocal action led to the development of wheel-driven lathes. The

wheel-driven lathe provided continuous, controlled rotation in one direction. This allowed constant

cutting, permitting turners to be more precise and efficient and enabled the use of harder

materials. Leonardo da Vinci was one of many to invent a continuous drive lathe, complete with

treadle, large flywheel, crankshaft, and a tailstock with hand-cranked screw adjustment. Stuart

King explains its operation in his article,

Short History of the Lathe

: "The crank,

linked to the treadle provided constant rotation whilst the momentum of the large flywheel ensured

the crank was carried over its 'dead spot'."

Pole lathes continued to be used almost unaltered from about 500 B.C. into the late Middle Ages,

until the inefficiency of its reciprocal action led to the development of wheel-driven lathes. The

wheel-driven lathe provided continuous, controlled rotation in one direction. This allowed constant

cutting, permitting turners to be more precise and efficient and enabled the use of harder

materials. Leonardo da Vinci was one of many to invent a continuous drive lathe, complete with

treadle, large flywheel, crankshaft, and a tailstock with hand-cranked screw adjustment. Stuart

King explains its operation in his article,

Short History of the Lathe

: "The crank,

linked to the treadle provided constant rotation whilst the momentum of the large flywheel ensured

the crank was carried over its 'dead spot'."

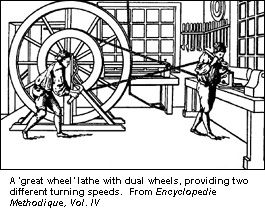

For heavy work the 'great wheel' was developed. The freestanding flywheels were often six feet or

more in diameter and were usually located some distance away from the actual lathe. One or two men

were employed in turning the wheel, driven by a large cranked handle, while the turner was left free

to work. A connecting cord or belt turned smaller, often stepped pulleys at the lathe and could be

moved to select from a number of available gear ratios.

For heavy work the 'great wheel' was developed. The freestanding flywheels were often six feet or

more in diameter and were usually located some distance away from the actual lathe. One or two men

were employed in turning the wheel, driven by a large cranked handle, while the turner was left free

to work. A connecting cord or belt turned smaller, often stepped pulleys at the lathe and could be

moved to select from a number of available gear ratios.

In 1678 Joseph Moxon extolled the advantages of the wheel-driven lathe in

Mechanick Exercises

:

"Besides the commanding heavy Work about, the Wheel rids Work faster off than the Pole

can do; because the springing up of the Pole makes an intermission in running about of the Work;

but with the Wheel the Work runs always the same way; so that the Tool need never be off it,

unless it be to examine the Work as it is doing."

Later versions of the wheel-driven lathe were powered by animals. A mule or horse was hitched to

the end of a pole running out from a central shaft on an outdoor device. The animals walked around

and around, rotating the main shaft. With a series of heavy gears, the central shaft greatly

increased the speed while a smaller shaft brought the power out through a housing on the ground.

The housing, connected to another heavy unit, caused a flywheel to spin at high speed. As long as

the mules or horses pulled the pole, the pulley operated the device from a drive belt. If more

power was required, another animal was added. Other wheel-driven lathes incorporated a water wheel

rather than animals.

In 1769 Englishman James Watt sparked the Industrial Revolution with his improved version of the

steam engine. A few years later, in 1774, another Englishman, John Wilkinson, modified the lathe

and patented a precision cannon-boring machine which made efficient steam engines possible. The

steam engine cylinder could not be manufactured until machine tools capable of producing accurate

parts had been devised; the interior size of the cylinders had to be precise so steam could not leak

between the cylinder and piston. Wilkinson's new boring machine provided the accuracy required for

the detailed measurements crucial to Watt's design.

In 1751, French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson built an industrial lathe with an all-metal sliding

tool carriage that was advanced by a long screw. In 1797 Henry Maudslay in England and David

Wilkinson (no relation to John Wilkinson) in the U.S. almost simultaneously improved upon de

Vaucanson's lathe by adding a sliding tool carriage geared to the spindle, enabling it to move at a

constant speed in synchronicity with the spindle. This allowed the cutting of accurate and

repetitive screw threads, permitting the production of identical parts necessary for mass production

techniques, as well as standardization of screw threads and interchangeability of nuts and bolts.

In 1751, French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson built an industrial lathe with an all-metal sliding

tool carriage that was advanced by a long screw. In 1797 Henry Maudslay in England and David

Wilkinson (no relation to John Wilkinson) in the U.S. almost simultaneously improved upon de

Vaucanson's lathe by adding a sliding tool carriage geared to the spindle, enabling it to move at a

constant speed in synchronicity with the spindle. This allowed the cutting of accurate and

repetitive screw threads, permitting the production of identical parts necessary for mass production

techniques, as well as standardization of screw threads and interchangeability of nuts and bolts.

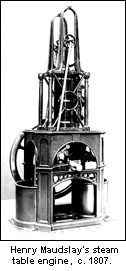

Maudslay further improved the lathe by incorporating the steam-powered engine. The steam engine

allowed large metal pieces to be worked much more quickly and accurately. Patented in 1807, his

compact steam table engine - named after the form of the frame that supported the cylinder - proved

particularly useful in providing power to small workshops and factories, as it did not require a

separate engine house. It was produced in large numbers in sizes varying from 1.5 to 40HP by a

variety of manufacturers until around 1850.

Maudslay further improved the lathe by incorporating the steam-powered engine. The steam engine

allowed large metal pieces to be worked much more quickly and accurately. Patented in 1807, his

compact steam table engine - named after the form of the frame that supported the cylinder - proved

particularly useful in providing power to small workshops and factories, as it did not require a

separate engine house. It was produced in large numbers in sizes varying from 1.5 to 40HP by a

variety of manufacturers until around 1850.

In 1819 Thomas Blanchard developed a reproducing lathe for the mass production of rifle stocks. A

large drum turned a friction wheel that traced the contours of a three-dimensional template and a

cutting wheel that followed the movements of the friction wheel to make an exact replica of the

pattern in wood. The lathe enabled an unskilled workman to turn very complex and highly detailed

shapes extremely quickly, and to easily produce identical irregular shapes.

In 1819 Thomas Blanchard developed a reproducing lathe for the mass production of rifle stocks. A

large drum turned a friction wheel that traced the contours of a three-dimensional template and a

cutting wheel that followed the movements of the friction wheel to make an exact replica of the

pattern in wood. The lathe enabled an unskilled workman to turn very complex and highly detailed

shapes extremely quickly, and to easily produce identical irregular shapes.

The first successful internal combustion engine was patented in 1860 by Jean Joseph Etienne

Lenoir of Belgium, and by the turn of the nineteenth century 'oil engines' were manufactured in

small units of adequate power to be used in small factories and woodworking shops. As engines

improved and became more reliable, compact and affordable, they grew in popularity with individual

woodturners with small workshops.

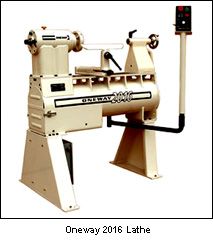

By the middle of the 20th century self-contained lathes with integral electric motors were

developed, making woodturning more accessible to the hobby turner. Today models with variable-speed

motors are common, enabling speed changes without having to manually move the drive belt onto

different pulleys. In addition, production lathes have evolved into computer-controlled machines of

extreme precision, capable of producing thousands of identical items a day in materials ranging from

balsa wood to titanium steel.

By the middle of the 20th century self-contained lathes with integral electric motors were

developed, making woodturning more accessible to the hobby turner. Today models with variable-speed

motors are common, enabling speed changes without having to manually move the drive belt onto

different pulleys. In addition, production lathes have evolved into computer-controlled machines of

extreme precision, capable of producing thousands of identical items a day in materials ranging from

balsa wood to titanium steel.

Despite continued advancements in technology throughout the centuries, however, the techniques

used to shape the wood remain the same. Consequently, the human elements of skill and talent are

still required to create wooden spindles, bowls, vessels, figures, ornaments and other

accessories.

Editors Note: Perhaps the most recent major innovation in woodturning is Craig Jackson's

development of his new

Easy Wood Tools

, which greatly

simplify how turning tools are used.

About the author: A former staff member at Highland Woodworking, Elena enjoys woodturning and was

the first editor of Highland's Wood News Online newsletter.

This article first appeared in the

December 2005 issue of

Wood News Online

.

Take a look at Highland Woodworking's full selection of

Woodturning Lathes

.