|

|

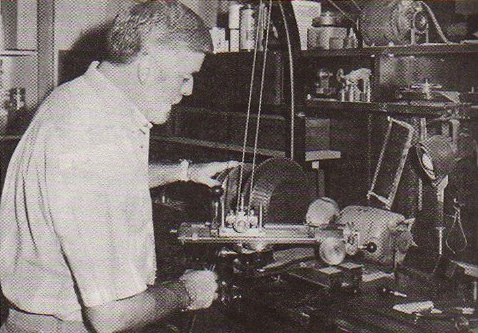

Ed Hernandez of New Orleans adjusts his Holtzapffel ornamental turning

lathe. Note partially completed bowl in chuck. (Photos are by Tom Frazer).

|

Ed Hernandez' Holtzapffel Lathe

by Tom Frazer

This article first appeared in the Fall 1987 issue of Wood News.

At ten paces, E.C. "Ed" Hernandez' Victorian-era Holtzapffel ornamental lathe doesn't appear terribly impressive. Frankly, it looks somewhat like an oversized but spindly treadle-powered sewing machine connected by looping belts to an overhead dentist's drill.

Yet, this "ultimate Rube Goldberg contraption" crafted 110 years ago in London by John Jacob Holtzapffel enables Hernandez to create exquisite works of art and to continue a hobby once pursued in their leisure time by Louis XVI of France and Peter the Great of Russia.

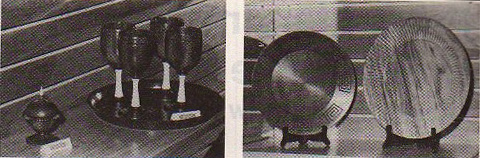

Using exotic tropical hardwoods like ebony or rosewood, Hernandez, 53, has employed his marvelous machine to produce graceful goblets, dainty ornamental boxes and artistically inscribed plates.

In 1985, Hernandez' wine glass of African blackwood and ivory won second place in competition sponsored by The Society of Ornamental Turners in the category for beginners with less than five years' experience. The event was held in Queen's Parlor in London. And early this year, Hernandez won first place with a cup and saucer made of three pieces of cocobolo wood at a Louisiana Arts and Crafts Guild competition in Baton Rouge. Cocobolo, a variety of rosewood, comes from Panama, western Costa Rica and Nicaragua.

For a number of years, the New Orleans native built apartment complexes and office buildings throughout suburban Metairie until recently fulfilling a personal dream by opening a woodcraft supply store called World of Wood. He first became interested in woodturning at age 16 while watching his grandfather, Emile P. Hernandez, Sr., use a lathe as a hobby. "When he passed away, I got his little cast iron lathe, and I've been turning ever since."

Hernandez' Holtzapffel lathe represents perhaps the ultimate development of the lathe - man's earliest machine tool which dates back possibly 3000 years. First used to make wooden bowls and similar objects, the lathe in its simplest form is a device that spins a piece of wood while the craftsman shapes the wood with a sharp cutting tool. Over the years, lathes became more sophisticated, and skilled artisans quickly turned out a multitude of utilitarian articles such as rocking chair spindles, lamps and newel posts. Eventually, modern mass production and the advent of new materials made man-operated lathes more-or-less obsolete for commercial purposes -- except perhaps for turning out today's custom-made baseball bats.

|

The Holtzapffel machine that the former developer acquired at a London auction several years ago is a rare remaining example of a custom-made ornamental lathe of the Victorian era, a time when artistic decoration was pursued wtih zeal and sometimes to wretched excess. From the 16th through the 19th centuries, particularly in Europe, ornamental turning was a popular art form that produced intricately decorated objects. Often they were of remarkably complex design -- such as the "Chinese celestial spheres" -- in which ivory was turned into lacelike spheres, one within another within another. In the 16th and 17th centuries, ornamental turning was practiced by numerous members of royalty and by their appointed artist-turners.

Holtzapffel, an engineer from Alsace, moved to London in about 1790, and in 1794, Holtzapffel and Co. begain making in its Charing Cross workshop what was to become regarded as the Rolls-Royce of precision tools. Customers were drawn from the upper classes who had the necessary money and leisure time to enjoy this esoteric hobby. And hobby it was, because the instruments were entirely too complex and slow to operate for profit. Indeed, Holtzapffel and his family felt compelled to write a five-volume work entitled

Turning and Mechanical Manipulation

that attempted to explain the intricacies of ornamental turning.

In the latter 19th century, British Army officers arranged for their ornamental turning lathes to be shipped along with them to the far reaches of the Empire. But by 1914, Europe was undergoing an upheaval, and the manufacture of ornamental turning lathes had ceased.

Hernandez got his first introduction to (and appetite for) a Holtzapffel lathe ten years ago at an arts and crafts show in Chicago. There he met Frank M. Knox of Manhattan, regarded as the doyen of ornamental turners in the U.S. "He had done some beautiful plates and some boxes that I thought were exquisite," says Hernandez. "We got to be friendly with him, bought one of his plates, and I started searching for one of those lathes."

That same year, 1977, was when he "really got interested" in woodturning, Hernandez recalls. He took a short course from a well-known turner named Russ Zimmerman in Putney, Vermont. There, Hernandez asked Zimmerman how he might acquire a Holtzappfel lathe of his own.

If not encouraging, the response turned out to be prophetic.

"He told me I would have a hard time finding one because most people who have one of these lathes usually die before they get rid of it," recalls Hernandez.

So about a year later, Hernandez joined The Society of Ornamental Turners, headquartered in Britain, which gave him access to the people who had these lathes. He began writing to the approximately 300 persons on the list, including those living in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. He started with the approximately two dozen Holtzapffel lathe owners in the U.S.

Finally a response came from a Richard Maud in England who informed Hernandez that two Holtzapffel lathes were expected to be auctioned in London. One was a machine owned by Fred Howe, considered the finest ornamental turner of modern times. Howe, Maud revealed, had suffered a stroke and was in poor condition. Should he die, his lathe was expected to be put on the auction block.

"Approximately a year later, Mr. Howe died," says Hernandez, "and I was able to go to England and acquire the lathe."

But not without considerable difficulty.

Even before Hernandez jumped into competitive bidding against 72 other hopefuls at Christie's auction house, he painstakingly checked out hundreds of disassembled parts and accessories to determine which part went with which lathe. This was necessary because, a century ago, the precision machines were not mass-produced. Likening a Holtzapffel to a modern Rolls-Royce or Rolex watch, Hernandez explains, "All of the lathes were made individually, and all the parts that fit on a particular lathe were numbered to correspond to that lathe. It took almost two years to make a lathe."

So with the help of an agent, Hernandez identified which lot numbers of parts to bid on, and eventually, was able to purchase Howe's lathe.

"Although my broker was seasoned at this type of work and was guiding me properly," Hernandez says, "there were some parts I failed to get: the parts, for example, that make the Chinese balls. I could have gotten those for relatively pennies."

Back in Metairie, it took Hernandez three months to clean and assemble the Holtzapffel, "and then try to figure out how to use it." Having previous experience with lathes and being mechanically inclined helped, he says. So did reading a set of four antique volumes written by engineers that gave him "a feel of how this machine worked." Exults Hernandez, "I tell you, experimenting with it has been unbelievable!"

|

|

Pictured above are four goblets of purpleheart and ivory along with a

small ring box of purpleheart, all turned by Hernandez on his Holtzapffel

lathe. The right-hand picture shows two of his decorated plates

which were turned on the lathe.

|

But try to imagine the problem. The crate that arrived from England contained not only the lathe itself but also a dozen boxes of accessories. "I have about 1100 different bits that fit into approximately 25 different cutting frames," Hernandez says. Accessories also include a tap and die set for making replacement screws, as well as a completely assemblage of sharpening stones and paraphenalia to sharpen all 1100 bits, each a different size and shape.

Hernandez clearly is impressed with becoming associated with an elite tradition. "The people who bought these lathes would be the people of means in those times," he says. "They had a lot of time on their hands and were able to understand the engineering aspect of ornamental lathe work. It was a hobby machine for the lords and princes that was made from the Renaissance to the Victorian era."

Fewer than 100 Holtzapffel ornamental turning lathes remain, and today Hernandez believes he's among only eight owners who actually use their machines. "Many are in museums, and many are owned by collectors. Lathe No. 2135 is in the Smithsonian Institution, and No. 1556 is in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Some are not complete working lathes, and all are foot powered, like an old-fashioned sewing machine," Hernandez says.

Like fellow members of The Society of Ornamental Turners, Hernandez took care to learn his lathe's "genealogy". "My lathe is No. 2325, and it was purchased for 100 pounds on January 4, 1877, by a Lord Overstone for Lewis V. Lloyd, Esq. And as a matter of fact, I have a copy of the invoice." The second owner was Thomas Herbert Edwards of Liverpool. When Edwards died, he left the lathe to his chauffeur, a Welshman named Griffiths. After trying for 10 years, Fred Howe finally persuaded Griffiths to sell the rare Holtzapffel. "Then through Christie's auction house, it came to me," says Hernandez.

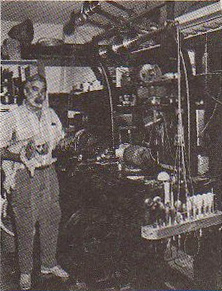

At his home in Metairie, Hernandez also has a top quality English Myford lathe, as well as an oversized lathe that was custom built to his own design (pictured below). With his largest lathe, Hernandez can turn bowls up to 44 inches in diameter!

Using his Holtzapffel lathe, Hernandez has manufactured about 100 pieces, some of which take about 40 hours to complete. Objects include plates, round boxes, goblets, chalices, and a cup and saucer. "The lathe has so many possibilities that my son and my son's son could use it for their lifetimes and never exhaust the designs that can be made," Hernandez says.

Thus far, Hernandez' tour de force is an ornamental pedestal box that consists of a round domed lid supported by a ring and five columns attached to a base. It is made in ten pieces of purpleheart wood which came from Central and South America and pink ivory wood that's native to South Africa. Hernandez liked his creation so much that he had postcards printed from a photograph of it.

In a philosophical context, Hernandez is fascinated with another aspect of his tool. "A lathe," he says, "is the only machine tool that can reproduce itself."