Hand Planes: Unlocking the Mystery

by J. Norman Reid

Delaplane, Virginia

Like many other woodworkers I decided early on I would be a "Normite" and bow to the superior

precision of power tools.

Hand tools

seemed just too imprecise and hard to master. But somewhere

along the way, I developed affection for hand planes and began to unlock the mysteries of their use.

Now, their secrets solved, they are a regular part of my woodworking practice. They can be for you

too.

Although a wide variety of

hand planes

are available on the new and used markets, most applications

involve what are known as "bench planes." The most practical of these, as denominated by the Stanley

numbering system, are numbers 3, 4, 4-1/2, 5, 6, 7 and 8. Together with a block plane, these make up

most of the planes you'll ever need. And you won't even need all these. At a minimum, you can do

perfectly well with one jointer plane (a #7, 7-1/2 or 8), one smoothing plane (a #3, 4 or 4-1/2) and

a block plane.

Three Essential Planes

Although it’s possible to build up a large stable of planes designated for specialized purposes, you

can do everything you need to do with just three essential planes—a block plane, a jointer and a

smoothing plane. My recommendations are a low-angle, adjustable mouth block plane like the

Lie-Nielsen

#60 ½

;

a

#7

,

#7 ½ low angle

or

#8 jointer

;

and a

#4

or

#4 ½ smoother

. Though you can

find restorable planes on the used market, you won’t go wrong by spending a little more for the best

quality, like Lie-Nielsen. Once you have these basic planes, you can fill in other, more

specialized planes as your needs require and your budget permits.

Bevel Down vs. Bevel Up Planes

Traditionally, hand plane blades were mounted in their bodies with the bevel facing down, toward the

wood. Recently, however, a number of planes have been introduced with the bevel facing up. Aside from some advantages in how the effective blade

angle can be changed by the angle at which the bevel is honed, the chief benefit of a bevel up plane

comes in setting it up for cutting. A bevel up plane has fewer parts, no chipbreaker or lateral

adjustment lever and is easier to set up. However, bevel down planes look more complicated than

they really are and they can be easily learned. Both types of planes work well. So, the choice is

yours.

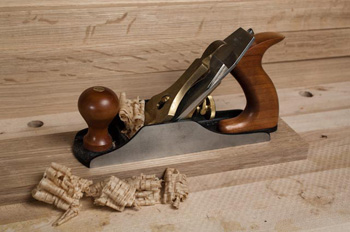

How They're Used

To plane rough boards smooth, start with the jointer. Its long bed rides over the board’s hills

and valleys and knocks them down as it goes. Continue planing until the board is dead flat. Once

you're there, switch to your smoothing plane and give it a few light passes to get everything nice

and, well, smooth. When any ridges left by the jointer are gone, you're done. If you are taking

your boards from a power planer, using a smoother is the only step you'll need to do.

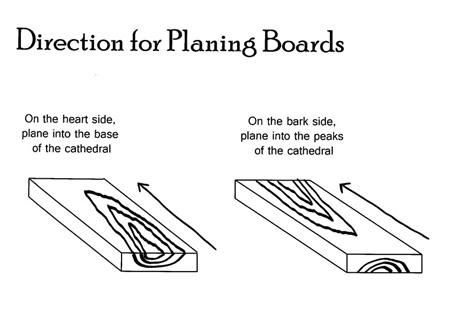

Reading Your Board

The direction you plane matters if you want to avoid tearout. You want to plane with the grain,

but on a rough board, how can you tell what that is? One method is to look at the edge of the board

to see which way the grain lies. You want to plane in the direction the grain is rising. The usual

analogy is to treat the board as you would the fur of cat--plane so the grain lies down. Another

method is to look at the end grain and identify the heart side of the board. It's the side toward

which the rings are bent. The outer side of the rings is the bark side. With the heart side facing

up, orient the board so the bottom or open side of the grain’s cathedral is facing you. Then plane

from the bottom of the cathedral toward its top. When you flip the board to the bark side, reverse

the board so you are planing into the peaks of the cathedral. This will ensure that you are always

planing in the right direction.

Flattening Uneven Boards

Unfortunately, rough boards don’t always come flat from the lumber yard. They may be cupped from

side to side, bowed from end-to-end or even twisted so adjacent corners are uneven. Check for these

conditions before you begin to flatten your board. Place cupped boards with the concave side down.

Then plane a valley down the middle of the convex side until it is even with the sides or a bit

lower. After that, plane the board diagonally until it is level on that side.

For boards that are bowed from one end to another, place the concave side facing down and, with

your jointer plane, make successive passes down the length of the board until you've achieved

flatness. You will get best results if you cut the board into shorter pieces before planing. This

reduces the amount of bowing that has to be removed. If the board is severely bowed, you may need to

start by planing crosswise to reduce the high spot to the level of the rest of the board before

planing along its length. Once you have one face flattened, turn the board over and work on the

ends, which will be thicker than the middle, to bring them down to the desired thickness.

Twisted boards present the biggest challenge. You may need to shim opposite corners so they will

be stable on your benchtop. Sight along winding sticks--perfectly flat sticks positioned at

different points on your board--to see where the high spots are. Mark these, then plane them down

until your winding sticks are in perfect alignment all along the length of your board.

Once you have one face flattened, plane the edges flat and perpendicular to the first face. This

is not as hard as it appears. Hold your plane as close to 90° as you can and take a few strokes.

Once the edge is smooth, test it with a square at several points. If one side of the edge is high,

center your plane over that side and take a couple more strokes. Repeat until the side is

square.

Final Thicknessing

With one face flat and the sides square to the face, use a marking gauge to scribe a line

indicating the thickness on all four edges. Then plane the board down to that line. If you have a

lot of material to remove, consider starting with a scrub plane, a narrow plane with a deeply curved

blade that excels at fast stock removal. Used Stanley scrub planes are widely available;

Lie-Nielsen

also manufactures one.

Planing the Ends

The final step is to plane the ends square to the rest of the board. Because you'll be cutting

end grain, extra care is needed. A low-angle block plane works well here. Work in from the leading

edge and plane to the center of the board, but avoid planing all the way across the board.

Otherwise, you risk tearout (spelching) at the trailing edge. You can aid cutting by moving the

plane with a circular motion, which slices the grain at an angle. Above all, keep your blade extra

sharp for the tough end grain. Best results are obtained by using a shooting board, which holds your

board against a stop and lets you take small shavings at exactly 90° to the rest of the board. You

can make your own shooting board.

That's all there is to it. By following these few rules and keeping your blades honed, you'll be

planing like a pro after only a couple of boards.

Click here to read more information about working with hand planes

Click here to find out more and purchase your own hand planes

J. Norman Reid is a woodworker specializing in 18th Century and Craftsman furniture. He

teaches hand planing in northern Virginia where he lives with his wife, four cats and a basement

woodshop full of tools in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

He can be reached by email at

nreid@fcc.net

.

Return to

Wood News

front page