BOOK REVIEW:

The Soul of a Tree - A Woodworker's Reflections

by J. Norman Reid

Delaplane, VA

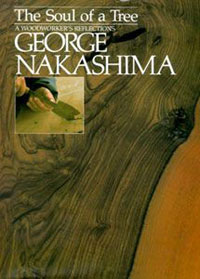

The Soul of a Tree

, George Nakashima's autobiography and philosophy, is a special

book about an extraordinary woodworker. It is, of course, an account of the story of his

life and the influences that led him to become the exceptional woodworker that he was.

But it is much more than that, for those influences—from his earliest years—developed

his deep reverence for nature and, in particular, for the many and varied species of

trees that inhabit our shared planet. And it is the expression of his philosophic views

about trees that forms the core and important message of this book.

Born in Washington State, Nakashima learned early to love the forests and mountains

of his native state. Leading groups, but often taking extended hikes alone, he deeply

contemplated the natural world he loved, learning to appreciate its beauty in all details

and the value of solitary communion with a part of the world much older than civilization

itself.

His chosen field was architecture, and after receiving his B.A. from the University of

Washington, he studied in France, was awarded a second degree, then completed his

Masters in Architecture at M.I.T. Following his studies, he began a long international

travel that was to further shape his philosophy, his life, and his eventual choice of

woodworking for his life's work. His first stop was in Paris, where he had earlier studied

architecture. There he worked in a music publishing house, leaving after a couple of

years for Japan and employment in an architectural firm. When the firm was contracted

to build a facility at the ashram of Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry, India, Nakashima

volunteered to lead the project.

At the ashram, he was deeply influenced by the personality of Sri Aurobindo and

eventually stayed on as a member, giving up his salary while overseeing construction.

He remained a number of years, receiving his Sanskrit name of Sundarananda, which is

translated into English as "One who delights in beauty." It was to be prophetic.

Eventually he made the hard choice between remaining at the welcoming ashram or

leaving for a different life elsewhere. With difficulty, he chose to return to Japan. There,

he met his future wife, Marion, herself an American-born teacher of English. They

returned to the U.S. to be married, just before Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of war.

In Japan he had become interested in woodworking and briefly operated a woodworking

shop in Seattle before he and his family, including newly-born daughter Mira, were

interned with others of Japanese ancestry in Idaho. Luckily, he met a fine

Japanese carpenter trained along traditional Japanese lines. From this carpenter,

Nakashima learned many of the skills of perfection that would stand him in good stead

throughout his career.

In 1943, he was allowed to leave the internment camp and resettle in New Hope, in

Bucks County, Pennsylvania. There he began woodworking, at first with hand tools

only, gradually adding machines. He was able to purchase a small plot of land, then

begin building a house. Eventually, this would grow into a much larger compound that

today comprises a number of studios, living quarters, warehouses and the Minguren

Museum.

Woven throughout his history, his exploration of the life cycle of trees and woods, and

the craftsmanship that went into the furniture he designed is his philosophy about the

value of trees and the use of wood. As Nakashima states, "Each flitch, each board,

each plank can have only one ideal use. The woodworker, applying a thousand skills,

must find that ideal use and then shape the wood to realize its true potentiality" (p. xxi).

To that end, he accumulated wood from exceptional trees from around the world,

holding as many as 10,000 boards in his sheds for as long as 10 years until the right

use for them was discovered.

Though Nakashima held reverence for the majesty of special trees, he believed also

that they should be used for the support and beautification of human life. A key part of

his philosophy was that, through careful craftsmanship, each felled tree could be given

a new second life that could rescue it from decay and preserve its value for the future.

He believed deeply that each piece should show only the highest quality craftsmanship.

And that craftsmanship, he also believed, was best attained by the Japanese, who

excelled in joinery techniques that were largely unknown in the West. The book shows drawings

of many of these joints and illustrates their complexity and suitability for fine work.

The book is well-illustrated throughout by Nakashima's drawings of trees, woods, and

furniture of his own design, such as his famous Conoid chair. Likewise, it includes many

color photographs of the New Hope compound, his lumber supply, and the logs they

derived from his furniture and production processes.

This inspirational book portrays the development of a true craftsman and shines with the

spirit of reverence for our chosen medium of working and the perfectionism of a master

craftsman. Woodworkers at all levels can well appreciate and learn from his life story

and his example. Especially for those woodworkers who seek a deeper awareness of

the meaning of our chosen vocations or avocations, this book is well worth reading and

contemplating.

CLICK HERE to order your copy of

The Soul of a Tree - A Woodworker's Reflections

J. Norman Reid is a woodworker, writer, and woodworking instructor living with his wife in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains with a woodshop full of power and hand tools and four cats who believe they are cabinetmaker's assistants.

He can be reached by email at

nreid@fcc.net

.

Return to

Wood News

front page