Project Idea: Goodrich Step-Stool

by Mark Miller

Waco, TX

My Great Uncle James Goodrich (LtCol USMC retired) made step stools for every child in the family; his

children, grand children, great-grand children, nieces, nephews, grand, and great-grand nieces and

nephews. Four generations in all. In my family, that's a bunch of stools. His design was solid and

simple to cut and assemble - about 9 inches high with an 8 inch by 16 inch stepping surface inlayed with

the child's initials. The gifts are perfect to help a child "reach and see" and as they grow older, they will

become a treasured family heirloom. With the passing of my Uncle Jimmy, I've stepped in and while I'll

never have his talent or woodworking confidence, I believe this tradition he created is important to

continue.

Unfortunately, my uncle and I never talked about the stools, how he made them, or the materials he

used. The base of the stool is formed from leg/sides joined by a center brace and a pegged through

tenon. The step is secured to the base with dowel pins.

A quick word about the materials list. There are some craftsmen out there who can develop a bill of

material from a plan with perfect confidence in what they'll use and what they'll waste. Well, I'm not

one of those guys and I'm not going to risk having to drive back across town for more wood for the sake

of maybe saving a foot or two. Further, my lumber yard serves commercial enterprises and won't

custom crosscut my one or two boards to length. I wrap all my excuses together in a package and top it

off with the belief that there's always a use for hardwood scraps. Take my materials list as that, and develop

your own to match your own excuses.

Materials List

-

Maple: 50" x 9"x 4/4

-

Walnut: 1/8" thin stock x 4" x 9"

-

Dowel pins: 6 at 3/8" x 1 ½"

-

Tenon pins: 1/2" walnut dowel rod

-

Walnut thin stock (1/8") 4"x 8"

-

Painter's tape

-

Glue

-

Sand paper (220 and 320 grit)

-

Finish of choice

-

4 rubber or nylon feet

Finally, there are many ways to cut wood and tools to help do it. My tools list describes the methods and

tools I use, but it should in no way limit anyone. If you don't have a scroll saw or band saw (I didn't

always have one), substitute a jig saw or coping saw. Mankind made furniture long before Muddy Waters invented

'lectricity.

Tool List

-

Planer

-

Table Saw

-

Radial Arm Saw

-

Scroll Saw

-

Drill

-

Dowling Jig

-

Sander

-

Router

-

Bevel Chisel

-

Square

-

Pencil or marking knife

-

Compass

-

Ruler

Cut List

-

(1) 16" x 8" (top/step)

-

(2) 8" x 8" (leg/sides)

-

(1) 4" x 14" (brace)

-

Thin stock for inlay initials

The step, two sides, and the brace add up to 46 inches. My planer takes a little snipe so I include four

inches, two at either end, to allow for that and the saw kerf. Wanting a final thickness of ¾", I plane

13/16" which leaves 1/16" to sand away.

First I rip the edges of the entire length

on the table saw to true the edges and use

the radial arm saw to cross cut the pieces.

I cut the snipe off one end, then cut 16"

for the step, 8" and 8" for the legs, and 14"

for the brace.

Back at the table saw, I set the fence at 8",

confirm it with a pine board, then rip the

step and legs. You might wonder why I

didn't rip the 50" piece to the final width

before I chopped it up with the radial arm

saw. This is because I have a small table saw and

the longer the board, the more likely I am

to let it wiggle. I find two-footers easier to

rip than four-footers. I adjust the rip fence

to 4", test it on some scrap, and then rip

the brace.

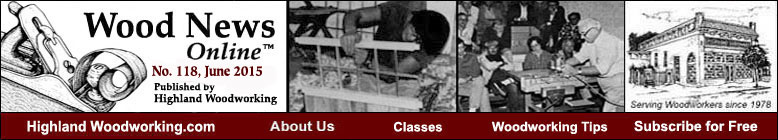

Leg/Side

|

|

Figure 1: Leg/Sides (2 ea)

|

Each leg/side has three characteristics to cut, the 1:8 taper or angle of the sides, the mortise, and the

arch at the bottom. Measure and mark both leg/side boards as shown in Figure 1.

When you cut the angles/tapers with a radial arm saw, it's 1:8 about 7 degrees. I cut one side then flip it over to

cut the other so I don't have to change the saw-arm setup. Now that the radial arm saw table is scored,

setting the angle is a breeze. I got there by sneaking up

on it with several practice cuts on scrap pine. The value

of a true-measured angle is aesthetic rather than critical;

I chose 1" in from the edges because it's easier to

center the step on the base during assembly.

Mark the mortises on front and back with a marking

knife, I use a small craft knife. This is more precise than

the finest pencil and cuts the top layer of wood fiber,

which greatly improves your chances of victory in chisel

combat.

Mark the arch at the foot seen in Figure 1 with a compass.

I use a scroll saw to hog out the middle of the mortise,

leaving a fine, thin 1/16" inside the scribed line to finish out with a very sharp chisel. The fit and

appearance of the mortise and tenon will very clearly show the sharpness of your chisels and the limits

of your patience.

I use the same saw to cut the arch at the bottom of the leg/side and a sanding drum on my drill press to

clean it out.

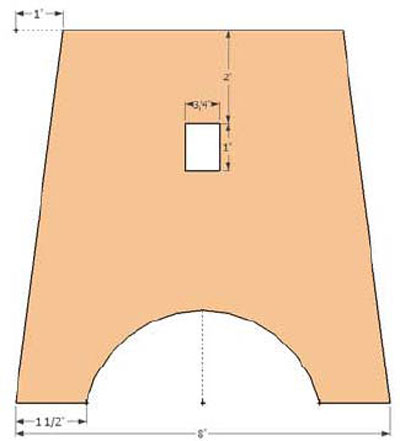

Brace

|

|

Figure 2: Brace

|

Making the brace is a matter of cutting the tenons, the arch at the bottom, and the holes for the pegs.

Mark the brace board like in Figure 2.

The accuracy in cutting the tenons shows

very visibly as gaps in the assembled

stool. Uneven shoulders above the

tenon will show as a gap between the

brace and the inside of the leg. A tenon

cut high or low on the brace will cause

gaps between the step and the "base"

parts of the stool. A marking knife and

marking gauge are well worth the

trouble.

Like the arch in the leg/side, there's no hard-

fast dimensions for the arch in the brace. I

measure in 1" from the shoulders and bend my

flexible steel rule and a shop-made gadget to

for the arch.

The little toggle is cut from a maple

scrap, the string is 550 chord I had

laying around and the stopper ball is

one of those plastic, spring-piston

thingies sold in craft stores used to

hold the gathering strings on a cinch

sack. Before that, I used the lid of my

turkey fryer. It's about the right size

and lays flat while you trace around

it.

For pins, I use a ½" walnut dowel. The little touch of color draws your eyes away from the step and to the

rest of the stool. Drill the dowel holes in the tenon set 1/16" back into the leg/side. Use a utility knife

and sand paper to "fit" the dowel to tightly hold the tenon through the mortise. I use a trial and error

method of "trim and try" until the fit is what I want. Improper fit may seem tight and sturdy but will cause

the leg/side to cant on the brace. Make sure you work patiently.

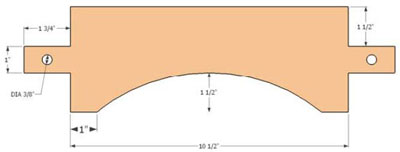

Step

|

|

Figure 3: Step

|

Aside from the inlaid initials, the step is nothing more than an 8" by 16" piece of maple. But for the

Goodrich stool, the initials are the whole point. While this isn't an article about router inlay techniques,

the top-level process is as follows:

Router Inlay

-

Print the initials on paper (I use my PC and ink jet printer)

-

Using carbon paper, transfer the initials onto the step as well as onto the inlay material. The outlines on

the step help you position the cut-out inlays.

-

Cut the initials from the inlay material.

-

Use carpet tape to fix the initials on the step.

-

With a sharp craft knife, carefully trace around each initial. This cuts the wood fiber and aids in keeping

the router "inside the lines."

-

With a thin putty knife, pry the letters off of the step.

-

Use a sharp pencil to draw inside the cut lines and use the eraser to eliminate any extra lines.

-

At this point, the letters are exactly traced onto the step.

-

Use a router and 1/16" bit to cut out the inlay recesses and the craft knife to clean out the corners.

-

Glue and press in the letters, and clamp over night.

-

Sand surface to flush.

|

I don't want to make more of it than there is, but the above procedure just touches the high spots of

free-hand router inlay. I'm self taught and I bet there are experts who can put together a really concise

and helpful article on the topic.

Pre-Assembly

I use a shop-made router table and ½" round over bit to break the edges everywhere but the mating

surfaces. Sand to smooth with 220 grit and you're ready to assemble.

Assembly

It goes together exactly as you'd imagine. Using a dowling jig to drill holes in the base, I put two in each

side and three across the brace. I prefer dowel centers to mark the corresponding locations on the

bottom of the step.

Glue and assemble the legs on the brace and lightly pin by gluing and tapping in the fitted walnut

dowels. Glue and assemble the step to the base. Clamp for 24 hours with bar clamps or cargo straps.

Remove the clamps, tap out the walnut dowel pegs, apply glue and tap them back in place firmly.

Finish

Apply the finish of your choice and keep in mind your intended use for the stool. My stools are mostly used by children. I spray three, thin coats of Deft satin poly, sanding between applications,

then rub the final coat with 0000 steel wool and apply a few coats of furniture wax.

Last step is to install the rubber

feet.

You can email Mark at

leathermech@yahoo.com

.

Return to

Wood News

front page