The Down To Earth Woodworker

by Steven D. Johnson

by Steven D. Johnson

Racine, Wisconsin

This month:

• Readers Respond to “It’s Hip To Be Square” (the

Shooting Board article

in the July Wood News Online newsletter)

• So You Want to Turn “Pro?”--- Be Careful What You Wish For

• Getting Into The “Zone”

Reader Comments: Last Month’s Shooting Board Article

We have received a number of comments about the “universal” shooting board adventure last month,

and quite a few have posed the question “Why use a shooting board at all?” The general thread of

these e-mails goes something like this:

“I have an extremely well-tuned [pick one: table saw, cross cut sled, radial arm saw, miter saw]

with an excellent blade and I get perfect 90-degree cuts --- why should I build a shooting board?”

These are excellent questions, so I will provide a few answers (pick the one you like the

best!).

First, there are projects pieces and cuts that I make on my trusty, well-tuned, upgraded-blade

(The

Forrest

Woodworker I

is outstanding) radial arm saw that are perfectly fine and are not ever

subjected to my shooting board. But, no matter how well tuned the saw or how good the blade, a tiny

bit of tear-out on the “blade-exit” side of the wood should be expected. That alone, if it is an

“appearance piece,” may be enough reason to turn to a shooting board for final trimming.

A shooting board also allows you to “sneak up” on the fit of a crucial piece unlike any saw. It

is difficult to shave off a few thousandths of an inch with a power saw, but with a well-tuned hand

plane, it is a piece of cake.

|

|

|

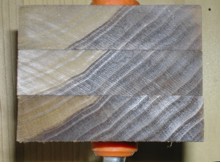

End grain finishing is another good reason. In the photo are three pieces of poplar cut from the

same board. The first piece on the top was cut on my RAS and then sanded with a sanding block

through a progression of grits. The middle piece is just a straight cut with no sanding, and the

bottom piece was cut and then shaved on my shooting board. While it may not be absolutely startling

(or apparent) in the photo, in person the difference in the stained finish is remarkable. The

finish on the “planed” end is more consistent, smoother, and more closely resembles the stain color

on the board face. You may also notice that in the first piece, even after sanding, there are still

saw marks. Not so in the piece that was planed. Note also the difference between the sapwood and

the heartwood. If it were your intent to even out the stain and go for a more uniform appearance,

it is obvious that starting with the planed piece would get you partway home.

One of my favorite power tools in the shop is my long bed 6-inch jointer. I wish it were 8 inches

wide, but that is another story. It is a wonderful piece of equipment, and many boards and many

pieces of furniture have benefited from its power and speed. I’ve built dozens of tabletops and

hundreds of panels with board edges power jointed. Then, one day, I finally broke down and ordered

a jointer plane. It is a 22-inch long behemoth and it took a little while to get the “hang” of

using it. Soon though, on a large table project, I decided to first power joint the board edges,

then give each edge a final pass or two with the jointer plane. The results, and the difference,

proved to be an epiphany.

After hand planing the pieces, I laid them side-by-side to prepare for the glue-up, and it was as

if the boards “sucked” themselves together. The fit was like nothing I had ever experienced. Two

hand-jointed edges together seem to “stick,” almost as if they need no glue. If you have never

experienced this kind of fit, you owe it to yourself to try.

There is another reason to build a shooting board. None of us “down to earth woodworkers” should

claim perfection (though I think some of you probably get pretty close!). There are times when the

end of a board cut to a perfect 90-degree angle does not fit in its intended home as well as a board

might if cut to, say, 89.9-degrees. Trying to make that paper-thin adjustment on the end of a board

with a power tool will be frustrating, dangerous, and probably yield less than optimal results. On

a shooting board, however, a shim between the fence and the work piece can give you the results you

need. The shim can be whisper thin, like a piece of paper or tape.

Convenience is another factor with shooting boards. Sometimes setting up for a perfect crosscut

with a power tool can take longer than grabbing a handsaw, cutting a bit outside the line, and then

trimming to square and a perfect fit on the shooting board.

Of course, all these reasons apply equally to 45-degree miter cuts. For these reasons, and more,

a shooting board is an indispensable tool in my shop, and probably will become important in your

shop, once you give it a try.

Turning Pro - Be Careful What You Wish For

In last month’s column I promised a hard look and some unusual advice for woodworking hobbyists

that want to turn professional – to “hang out your shingle,” so to speak. My apologies, but this

segment is delayed and will appear in the September issue of Wood News Online.

Turning pro is a subject that has been covered many times, but most articles seem to fall into

one of two categories: (1) How to go about the transformation, and (2) The joys of doing what you

love for a living. Next month we are going to look at an aspect of turning pro that you have

probably not considered, but many woodworkers have, in retrospect.

The subject is thought provoking, and simply deserves more space and more time. I guarantee it

will be worth the wait!

In The Zone

Only in the slow-motion instant replay could you really appreciate the pure athleticism, the

poetry of motion, and the extreme concentration. The defensive end ran stride-for-stride with the

receiver, their steps almost like a well-choreographed dance. The defender’s eyes were on the

receiver’s eyes, and in a split second, he leaped, pirouetted in mid-air, extended one hand, and

with his fingertips in perfect position, deflected the ball from the receiver’s hands. Asked later

about the inspiring play, he remembered every little detail. He was in the “zone.”

Ted Williams famously claimed that he could see the seams of the baseball as it left the

pitcher’s hand, could gage the rotation, and then virtually instantaneously adjust to fastball,

slider, or curve. When Ted was in the zone, time apparently slowed for him, and I have no doubt he

could see all those things, and more.

Some years ago I was fortunate to attend a concert featuring the great Yo-Yo Ma. During his

appearance, he performed solo – just him, his cello, and a simple metal folding chair in the middle

of the stage. Within seconds, it was glaringly obvious that Mr. Ma and his performance had entered

the “zone.” Every muscle of his body flexed and moved with every note, his face reflecting the

concentration and utter absorption by, and into, the music. His intensity became the audience’s

intensity, and we moved with the melody, strained with the difficult passages, smiled at the

sweetness of the sound, grimaced at the effort expended. Yo-Yo Ma’s zone had enveloped the audience

into its own zone. It was amazing. Then, the oddest thing happened.

During one of the most difficult portions of the piece, as Yo-Yo Ma’s body contorted and strained

with the difficulty, his chair began to slip backwards. It was only a slight movement, and

reflecting on the moment, I am sure that he was completely unaware the chair had moved, at least at

the conscious level. I am also quite sure he was unaware that his left foot subtly hooked the left

front leg of the chair and pulled it back into place as he played seamlessly, breathlessly, through

his incredible performance.

Is this what being in the “zone” is all about? Is it a complete loss of consciousness for the

outside physical world and absorption into and by the current task? Is it concentration of such

intensity that all else disappears, or at least becomes automatic and subconscious? Is it the

perfection of performance become so innate that the mind can perform other tasks without

distraction? Is being in the “zone” replicable? Can the “zone” be entered willingly, on command?

Does being in the “zone” require extraordinary skill or talent?

All these questions, and many more, were zigzagging through my mind while I was, quite unaware,

in the “zone,” myself, preparing some lumber for a new project. I guess this answers one of the

questions. There is obviously no extraordinary talent or skill required to find, enter, and enjoy

the “zone.”

The “zone” is a thoroughly enjoyable place to be. Elite athletes often describe the phenomenon

as a “perfect moment.” They use words like “fun,” “exciting,” and say they felt in complete control

and totally relaxed when in the “zone.”

It is not just elite athletes that experience the “zone.” High intensity stock traders often

describe being “in the pipe” while ferociously and accurately making high-speed trades on the hectic

stock market floor. A bass guitarist, playing perfectly between the melody and percussion say they

are “in the pocket.” Hip-hop performers that get into the “zone” and everything they say begins to

rhyme, say they are “flowing.” So, whether you are “in the groove,” “on the ball,” or just find

yourself “lost in what you are doing” you are probably in the “zone.”

Hungarian-born University of Chicago alum Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi is the architect of flow

theory. In his seminal work, “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience,” Csíkszentmihályi

theorizes that people are most happy when they are in a state of “flow” - which he describes as a

state of concentration or complete absorption with the activity at hand and the situation – what we

would describe as being in the “zone.”

Csíkszentmihályi says that everyone has experienced “flow” at times (I’m not convinced that is

true, by the way), characterized by a feeling of great absorption, engagement, fulfillment, and

skill - and during which temporal concerns (time, food, ego, self, etc.) are typically ignored. The

term “flow” comes from the fact that many people Csíkszentmihályi interviewed described the

condition as a current of water carrying them along in their activity.

It has been said that while creating the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo worked for

days at a time, not stopping for food or sleep, until he finally passed out. After awakening

refreshed, he immediately reentered the “zone” and again became completely immersed in his work.

For most of us though, being in a state of “flow” or “in the zone,” is a relatively brief event,

although it is hard to judge the actual length of the event, since time does truly seem to stand

still, race along, or otherwise become irrelevant.

In an interview with Wired Magazine, Csíkszentmihályi described flow as "being completely

involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement,

and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is

involved, and you're using your skills to the utmost."

So, if you have experienced being in the “zone,” or in a “flow” state, you know the power and the

enjoyment, the reward and the feeling. Many describe it as euphoric, joyous, and even rapturous.

I’ve been there, enjoyed it, and want more. Is there a way to force oneself into the “zone?”

Csíkszentmihályi identified ten factors that accompany the flow experience:

-

Clear goals. Goals are clear cut, able to be easily envisioned and skills are aligned

(the goal is neither too hard or too easy).

-

Concentration.

-

Self-consciousness disappears. Csíkszentmihályi is a very positive guy and seems to indicate

that self-doubt can prevent flow.

-

Time distortion. A person experiencing flow will usually also experience a distorted sense

of time. For some, time flies by unnoticed while in a flow state, for others time slows - think

of Ted Williams seeing a 90 MPH baseball pitch in slow motion.

-

Instantaneous direct feedback. The basketball forward who senses and reacts to an opponent

behind him may be said to have “eyes in the back of his head,” but he is actually more likely to

be “in the zone” where sensory feedback is heightened.

-

Balance between ability and challenge. A task too easy can become repetitive and boring.

We are more likely to enter a flow state if the challenge is aligned with our abilities, but is

not too easy. It appears that a goal slightly exceeding the skill level can also lead to the

flow state. This is what we might commonly refer to as a “stretch goal.” A boring task leads

to distraction, a “stretch” task hones concentration.

-

Being in control. Describing the flow state almost invariably includes a feeling of being

in command, in total control.

-

The activity is intrinsically rewarding. Ever heard someone say they enjoy hand-planing a

board? While it may be more work than a power planer, it can also be immensely rewarding.

Regardless of the caloric expenditure, being in the “zone” almost always involves doing

something you love, not for the glory or the outcome, but for the “something” itself.

-

A lack of awareness of bodily needs. Do you get into the “zone” and forget to eat? Have

you ever left a cup of coffee to get cold because you were engrossed in some shop activity?

-

Complete absorption. In the flow state, outside stimuli often recedes and one can become

completely unaware of distraction. Focus narrows significantly to the activity at hand. Often

in the shop I tune the television or radio to a program I like, then realize, some time later,

that a program I really dislike is now on, and I didn’t even notice.

There is a great deal of overlap in Csíkszentmihályi’s list. Absorption is a product of, or

companion to, concentration, and the narrowed focus of absorption lends itself to time distortion

and a feeling of being in complete control. Whether or not the list might be pared down a bit by

merging overlapping conditions, attempts to document the factors that accompany flow may also help

us identify the factors that might help us willingly achieve flow. Not to relentlessly pound this

point, but being in the “zone” is a remarkably pleasurable experience, and if there is a way to

encourage and induce the flow state, I intend to find it.

|

A warm day, some cool music,

a sharp plane, some crazy curly maple,

and long

unbroken shavings…

nothing gets me in the “zone” faster!

|

In the Down to Earth Workshop, getting into a flow state, or in the “zone” happens fairly

frequently, but at least so far, not by design --- it just happens. It has happened while sketching

a new design, while hand cutting dovetails, while milling parts at the router table, while cleaning

the shop, and, believe it or not, even while sanding. The experiences are all similar. Time seems

to stand still, while flying by. Background noise (radio, TV, machinery noise) disappears.

Concentration is at hyper levels, physical exertion is inconsequential, and there is a great sense

of satisfaction. Not to sound too new-age cosmic or to revert to late-sixties’ hippie-speak, but

while smooth-planing a board recently, it felt as if I had become “one” with the wood. Once while

rough milling lumber for a project, I could see with startling clarity the grain flow in the future

finished piece from the raw bits of wood on my bench – I simply “knew” from which piece of wood each

piece of the project should be cut. It was “like, far-out, man!”

So how can I make this “flow” experience happen more often? Psychologists tend to agree that a

person cannot force him- or her- self into a state of flow. In fact, they mostly agree that we

cannot even predict when it is going to happen. While there is probably evidence and science to

back up this position, I refuse to accept the premise. I have become a “zone junkie.” Being in the

zone is intensely pleasurable, and I need more! The mind is a powerful tool, and we have tapped into

precious little of its potential. So, if naysayers say we cannot force ourselves into a flow state,

we can certainly set up the conditions which are conducive to, and usually accompany, being in the

“zone” and hope for the best.

To start, we know conditions that are antithetical to being in a flow state. Basically, any

negative emotions should be avoided/eliminated. Self-consciousness, anxiety, worry, boredom, apathy

must be displaced by relaxation, a feeling of being in control, confidence, and enjoyment of the

activity for the activity’s sake. The goals we set for ourselves should not be unattainable, but

should also be a “stretch,” so that we avoid tediousness and boredom.

Conscious distraction should be removed, so that our unconscious (or subconscious) can control

our concentration and our physical actions. A big ticking clock on the wall in front of our

workbench might not be conducive to losing our sense of time while we are carving or cutting.

Drinking twelve cups of coffee before starting a complicated glue-up might not allow us to ignore

our bodily functions and will likely prevent us entering the flow state (at least the flow state we

desire!).

The activity in which we immerse ourselves, hoping to achieve the flow state, should be an

activity we intrinsically enjoy. The concept of “intrinsic enjoyment” requires a little

explanation. Question a few woodworkers “What do you enjoy about woodworking?” and the answers will

range from the superficial (“Everything!”) to the bizarre (“I really love sanding a piece before

applying the finish.”) but you have to dig down deep in the questioning. Get specific. Do you enjoy

picking a design or designing the piece? Do you enjoy buying the wood? Do you enjoy dressing the

wood? Do you enjoy cutting the parts to size, cutting the joints, or gluing up the assembly? Do you

enjoy the finishing, or do you just enjoy “being finished” and delivering the piece to the happy

recipient? This is where the rubber hits the road, folks, because unless there is a part of the

process somewhere between buying the lumber and delivering the finished piece that you thoroughly

enjoy doing, you are not going to find yourself in the zone, no matter how much you might try.

The reality is, some woodworkers enjoy buying tools and building their dream shop more than they

enjoy actually working the wood. You might get in the “zone” looking at tool catalogs, but you will

never get in the “zone” cutting, carving, or turning unless there is a facet of woodworking that you

intrinsically enjoy.

For me, there are several aspects of woodworking that I intrinsically enjoy. Turning rough-cut

lumber into milled-square stock is a kick. I love to see the grain emerge from beneath the aged,

dirty, saw-scarred surface. I love to see a cupped, bowed, twisted board transformed into square,

straight, and beautiful. I also love the act of planing by hand. There is nothing, in my opinion,

that gets you closer to the wood. The whisper-thin see-through shavings effortlessly shooting up

through the mouth of the plane make an almost imperceptible sound, like breeze and bough in a quiet

forested valley. Gluing up a project almost always results in a “zone” experience, too. There is

no frenzy or drama, because I have rehearsed it, but there is concentration and focus. Time becomes

suspended, yet races ahead, and there is a real and palpable pleasure in seeing the almost-finished

piece come together. I enjoy starting a project with the roughest of sketches and a measurement or

two, and designing as I build, mostly in my head. I have never been fond of following a plan,

assembling a kit, or even drawing my own plans in detail. I get in the “zone” designing as I go.

And, admittedly, I enjoy buying tools! I must be in the “zone” when the hours disappear as I read

catalogs, literature, and reviews and ponder my next purchase.

When you were last in the zone, what were you doing? Whatever it was, that is one of the things

you enjoy most. Do a little honest self analysis to determine what aspects of this great hobby you

enjoy most, set up the conditions that will be most conducive to entering a flow state, then get to

work! Chances are, you will get into the zone pretty quickly, stay blissfully there, and can return

to that great “zone” anytime you choose. Call me an optimist, but I believe you can willingly enter

a flow state and get in the “zone.” Great things happen in the “zone!”

Let me know if you have found the method to get purposefully into the “zone.” What helps you get

to this special place? Is there a technique, a certain atmosphere (music, incense, whatever), or a

time of day that works better? Is it activity-specific, or is it something else?

As promised, next month a unique spin on the concept of “turning professional” and more will be

discussed. Believe it or not, another book will be reviewed, and some feedback on the “gestalt”

experience from last month’s column. Until then, I look forward to hearing from you. Enjoy, stay

safe, and keep it “down to earth!”

Steven Johnson is recently retired from an almost 30-year career selling medical equipment and

supplies, and now enjoys improving his shop, his skills, and his designs on a full time basis

(although he says home improvement projects and furniture building have been hobbies for most of his

adult life).

Steven can be reached directly via email at

sjohnson13@mac.com

.